Countless people walk through Vancouver’s old neighborhoods each day, unaware of the history beneath their feet. After the Great Flood of 1894 washed away much of the city’s wooden sidewalks with the swift rise of the Columbia River, residents began calling for more durable sidewalks.

Still, it wasn’t until 1908 that Vancouver took decisive action. On January 2 of that year, Mayor E.M. Green addressed the City Council, recommending that all new sidewalks in the business district be constructed of concrete.

Over the following months, contractors were hired to replace aging wooden sidewalks, tackling the work one street at a time. By December 1908, new municipal regulations officially condemned the old wooden sidewalks and required all new sidewalks to be built of cement or artificial stone.

The city’s sidewalk overhaul created a boon for contractors, attracting not only local firms but also builders from Portland. At the time, it was common for contractors to sign their work by stamping their name and the year into a corner of the freshly poured sidewalk.

This map is my attempt at documenting Vancouver’s remaining historic sidewalk stamps. I’ve tried researching the many sidewalk contractors that have left their mark on Vancouver, but little information is available on many of them.

Elwood Wiles

Elwood Wiles was a prolific cement contractor who left his mark—quite literally—on the sidewalks of both Portland and Vancouver in the early 20th century. Born in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1874, Wiles moved to Portland with his family in the 1880s and began working in the construction trades by the turn of the century. He quickly established himself as a skilled sidewalk and curb builder, operating during a time of rapid urban growth and infrastructure upgrades throughout the region.

Though based in Portland, Wiles regularly crossed the Columbia to take on contracts in Vancouver. With the city’s 1908 sidewalk overhaul creating steady work for cement contractors, Wiles was one of several out-of-town professionals brought in to meet demand. His sidewalk stamps—typically reading “Elwood Wiles” along with a date—can still be found embedded in Vancouver’s older neighborhoods.

What sets Wiles apart is the wide geographic footprint of his work. In Portland, his stamps appear in eastside neighborhoods like Irvington and Alameda. In Vancouver, his work helped lay the foundation—literally—for a modernized downtown and residential grid. Though not much personal information survives, Wiles’ enduring stamps are a testament to his role in shaping the concrete legacy beneath our feet.

S.P. White & Co.

S.P. White had many municipal contracts for installing cement sidewalks in Vancouver during this time period. He was also Vancouver’s first street commissioner, being chosen by Mayor Green in December, 1909

Kampe & Co.

Kampe & Co. was a partnership between Alfred Alex Kampe and Clement Scott. While Kampe & Co. installed cement sidewalks for the city, they did much more than just sidewalks. In the April 26, 1920, issue of The Columbian newspaper, Kampe & Co. advertised sidewalks, cisterns, retaining walls, silos, basement digging, road work, excavating, street paving & concrete lamp posts. Their first contract with Vancouver was for grading and graveling improvements on S St. from St. Johns Rd. to the city limits. They advertised heavily in the Columbian newspaper, first with classified ads, then later with larger business ads. Alfred Kampe and Clement Scott dissolved their partnership on October 7, 1921

Alfred Kampe was born in Sweden on May 29, 1880. He married Sophie Marie Johnson. Alfred Kampe passed away on January 15, 1943.

Clement Scott moved to Vancouver from New York City in 1905. In New York, he was employed in building tunnels under the Hudson River. He also worked as a pipe fitter, working his way up to paymaster on the big railroad bridge. In 1910, Scott organized the Clarke County Harvest Festival which drew in over 40,000 visitors.

In 1910, Clement Scott purchased the Red Ash Coal Company starting with just one employee. He build the business to become the largest fuel operator in S.W. Washington and employing 30-50 men with an annual payroll of over $50,000.

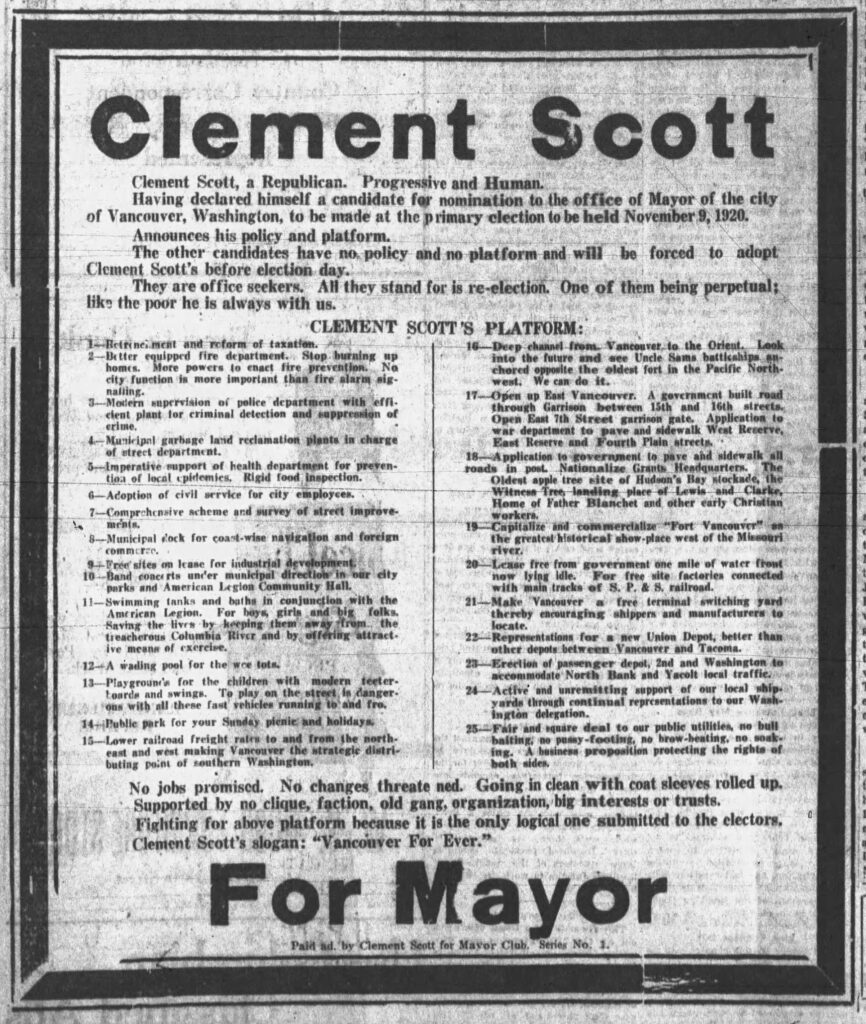

In the lead-up to Vancouver, Washington’s mayoral election held on November 9, 1920, Clement Scott emerged as a well-known candidate. A prominent Elk and local civic leader, Scott served as the president of the Washington State Association of Elks, past exalted ruler of the local lodge, and president of the Chamber of Commerce. His campaign was energetic—he spoke to thousands in streetcars, barber shops, and restaurants—and while straw polls often favored his opponent John P. Kiggins, Scott occasionally led in one.

Ultimately, however, it was John P. Kiggins who triumphed, winning the election and beginning a second term as mayor of Vancouver, Washington. Previously first elected in 1909, Kiggins went on to serve multiple nonconsecutive terms, becoming one of the city’s most enduring civic leaders.

Bechill Bros.

The Bechill Bros. were sued in Superior Court, along with the city of Camas, by R.D. Crowe for $400 for a breach of contract on a grading project.

Raymond

The Raymond sidewalk stamp traces back to R.C. Raymond, but what makes his work stand out in Vancouver, Washington, is the timing. His stamps don’t show up on street corners until the mid-20th century—specifically in 1945 and 1950. That’s decades after Vancouver’s big sidewalk boom, which kicked off in 1908 when the city pushed hard to modernize its streets.

Who exactly was R.C. Raymond? That part remains a bit of a mystery. The October 22, 1945 edition of The Columbian gives us one of the few solid clues: a permit issued to R.C. Raymond for 150 feet of sidewalk and curb at 3209 Z Street. Beyond that brief mention, the record falls quiet. What we do know is that the surviving sidewalk stamps across Vancouver trace directly back to Raymond, leaving us with more questions than answers—and just enough intrigue to keep his story alive in the concrete.

What’s most telling is the context—this wasn’t part of a citywide contract or municipal improvement project. It reads more like a private sidewalk job, maybe tied to a homeowner or small property upgrade. And interestingly, a review of the period’s newspapers shows no record of R.C. Raymond ever landing a city sidewalk contract. His legacy, at least in the sidewalks we can still find, seems to live in those smaller, more private projects that slipped in long after Vancouver’s major wave of concrete went down.

M.E. Kilkenney

While M.E. Kilkenney had many sidewalk contracts, I couldn’t find any information on the contractor.